Tagged With ‘oakmoss’

Guerlain

Derby

21 August, 2015

What a great perfume this is. Rich and complex yet totally wearable, Derby smells of old-fashioned luxury and style. It’s the kind of perfume that should have been name-checked in The Great Gatsby (surely the worst-written major novel of the 20th century), and yet it was first launched as recently as 1985, when electropop ruled the airwaves and shoulder-pads the size of aircraft carriers filled the pages of the fashion magazines.

What a great perfume this is. Rich and complex yet totally wearable, Derby smells of old-fashioned luxury and style. It’s the kind of perfume that should have been name-checked in The Great Gatsby (surely the worst-written major novel of the 20th century), and yet it was first launched as recently as 1985, when electropop ruled the airwaves and shoulder-pads the size of aircraft carriers filled the pages of the fashion magazines.

It was created by Jean-Paul Guerlain, the last member of the family to run the brand and a great perfumer in his own right: his other triumphs include Habit Rouge, Chamade and the fantastic Vétiver. Derby smells like crushed aromatic herbs when you first spray it on: rosemary and lavender with a hint of mint, but mixed with more exotic things like patchouli and sandalwood. Mace and pepper add a tiny touch of spice, while oakmoss, leather and vetiver give it extra depth and staying-power. After a while it smells more leathery than anything else, though still with herbs and spices mixed in – the scent of a Greek mountainside in summer.

For a long time Derby was quite hard to track down, which added to its mystique, but in 2005 Guerlain relaunched it as part of its Parisiens collection, at which point is was probably (though of course perfume companies never tell you these things) slightly ‘tweaked’ to change some of its ingredients (such as oakmoss) to comply with EU legislation. In 2011 it was repackaged in what I think is a rather cheap-looking balsawood frame, and its price went up as well: today it’s one of Guerlain’s most expensive fragrances, which I think is a shame, as it deserves to be widely worn.

Christian Dior

Jules

Sage isn’t everyone’s favourite herb, though turkey stuffing wouldn’t the same without it. It’s used less often in perfumery than in cooking, but Jules shows what a great ingredient it can be in the hands of a brilliant perfumer.

Sage isn’t everyone’s favourite herb, though turkey stuffing wouldn’t the same without it. It’s used less often in perfumery than in cooking, but Jules shows what a great ingredient it can be in the hands of a brilliant perfumer.

The ‘nose’ in this case was Jean Martel, who worked for the French fragrance company Givaudan in the 1970s and 1980s and deserves to be far better known, not least because he also created that 1970s classic, Paco Rabanne for Men.

Jules was launched in 1980, with a brilliant advertising campaign featuring posters by René Gruau, arguably the greatest fashion illustrator of the last century, which helped the first bottles sell out in record time. Martel combined sage (which has a slightly catty smell) with cedar and other things like wormwood, lavender and bergamot. To me the result smells like sage and slightly peppery leather, though there’s a long list of other ingredients, including cumin, sandalwood, oakmoss, jasmine, musk and rose.

Despite its initial success, Jules has since been overshadowed by the success of Kouros, which was launched the following year. Created for Yves Saint Laurent by the brilliant Pierre (Cool Water) Bourdon, Kouros shares Jules’ clean / dirty / sexy character, and both scents belong to the same fragrance ‘family’, the fougères – a style of perfumes, usually aimed at men, based on a combination of lavender and coumarin (originally derived from tonka beans but usually synthesised).

Of course, Kouros’ ongoing popularity may be because it’s inherently superior to Jules, but actually I think it’s more to do with the fact that over the years Kouros has benefited from regular advertising, while Dior seems to have forgotten that Jules ever existed, which I think is a terrible shame.

To make matters worse, while you can buy Kouros pretty much anywhere, Jules has become ridiculously hard to find: I don’t know anywhere in the UK that sells it, and even in Paris the only place that seems to stock it is the department store Bon Marché, though you can buy it from Dior’s French website. Given Dior’s apparent lack of interest, it’s a wonder it hasn’t been discontinued, but I’m glad it’s still on sale, even if it’s now a rarity.

I can only hope that one day they decide to invest in promoting it again and making it available to all – but in the meantime if you want something special that very few other people will have, get over to Bon Marché.

Chanel

Pour Monsieur

7 July, 2015

I’ve loved Pour Monsieur for decades now, so it was a bit of a surprise when I realised that I hadn’t reviewed it up till now. But actually I think that tells you something about the fragrance itself, which is so discreet that it’s all too easy to overlook – and that’s a real shame, because it’s a wonderful thing.

I’ve loved Pour Monsieur for decades now, so it was a bit of a surprise when I realised that I hadn’t reviewed it up till now. But actually I think that tells you something about the fragrance itself, which is so discreet that it’s all too easy to overlook – and that’s a real shame, because it’s a wonderful thing.

Pour Monsieur smells softly spicy when you first spray it on, but soon you also start smelling its mossy, herbaceous base. The spiciness comes partly from cardamom, and the woodiness is a mixture of oakmoss (actually a type of fragrant lichen) with tiny amounts of cedarwood, resinous labdanum (a kind of cistus) and earthy vetiver.

Chanel’s first modern men’s fragrance, it was conjured up by the perfumer Henri Robert and launched in 1955. Robert, who was born in 1899 and died in 1987, took over at Chanel after the retirement of the legendary Ernest Beaux, and went on to launch Chanel No19 in 1970 and Cristalle in 1974.

Pour Monsieur is one of the best examples of the perfume style or ‘family’ known as chypre, which derives from the French for Cyprus (the island rather than the tree), presumably inspired by the scent of Mediterranean herbs and shrubs baking in the sun. The basic combination – first popularised by François Coty in a 1917 perfume of the same name – combines bergamot, oakmoss and labdanum.

There have been endless variations on the theme since, but few of them match Pour Monsieur for sheer class; even its packaging is beautifully cool. Though it’s not an expensive perfume, it is redolent of luxury in its quiet complexity, like the deceptively simple face of a Patek Philippe watch. This is insider luxury, if you like, which is all about discretion and restraint rather than ostentation and excess.

The upside – in a perfume or a Patek Philippe – is that not everyone will recognise what you’re wearing. And while Pour Monsieur lasts a long time on the skin, it’s one of those fragrances that doesn’t carry far, so if you’re looking to impress it probably isn’t for you. But if wearing something wonderful makes you feel more self-confident and assured, then I can think of few better perfumes to buy.

Geoffrey Beene

Grey Flannel

23 February, 2015

The American fashion designer Geoffrey Beene died of cancer in 2004, but Grey Flannel, the perfume he commissioned from the French fragrance company Roure in the mid-1970s, lives on, and that’s something to be grateful for, as it’s a very appealing scent – even in its current, cheaper incarnation.

The American fashion designer Geoffrey Beene died of cancer in 2004, but Grey Flannel, the perfume he commissioned from the French fragrance company Roure in the mid-1970s, lives on, and that’s something to be grateful for, as it’s a very appealing scent – even in its current, cheaper incarnation.

Created by an otherwise little-known perfumer named André Fromentin, Grey Flannel was launched in 1975 (or 1976, depending on which perfume authority you believe; I’m often surprised how much confusion there seems to be around recent perfume history). Grey flannel was Geoffrey Beene’s signature material, but fortunately that’s not what his first men’s perfume smells of.

In fact Grey Flannel smells of violets, which seems like a weirdly feminine thing to choose for men, yet the clever thing about violets – or to be more precise, about violet leaves – is that as well as smelling sweet they also have a certain woodiness, which makes their scent far less girly than, say, lily-of-the-valley or rose.

Fromentin’s skill was to take this violet-leaf fragrance (which was successfully synthesised in the early 20th century) and mix it with fresh-smelling ingredients such as galbanum (which smells like green pea-pods) and bergamot (one of the most important citrusy components of the classic men’s eau-de-cologne), but also with typical ‘masculine’ woody smells such as oakmoss (actually a kind of lichen), cedar and vetiver.

The result is a deep, rich perfume that combines sweetness and woodiness in equal measure: it’s too sweet for some, but I love it, even though it’s been reformulated in recent years, presumably with cheaper ingredients – though for once at least some of the savings have been passed on to us, the customers, for Grey Flannel is one of the best-value perfumes you can buy.

Hermès

Equipage

14 July, 2014

Equipage is a perfume I hadn’t smelled for years. I had a bottle long ago, but when it ran out I never got round to replacing it. Actually I’d forgotten how good it smells, so I’m delighted to have it back. It’s as timeless and well made as a piece of Hermès saddlery, and it even has something of the same comforting, leathery smell.

Equipage is a perfume I hadn’t smelled for years. I had a bottle long ago, but when it ran out I never got round to replacing it. Actually I’d forgotten how good it smells, so I’m delighted to have it back. It’s as timeless and well made as a piece of Hermès saddlery, and it even has something of the same comforting, leathery smell.

The first Hermès perfume to be aimed at men, Equipage was created by Guy Robert, one of the leading perfumers of his generation. You could say that Robert had perfume in his blood. He learned his trade in Grasse, once the world capital of perfumery and still an important production centre today. His uncle, Henri Robert, succeeded Ernest Beaux as perfumer-in-chief at Chanel, where he created No.19 and Pour Monsieur.

Equipage shares much of its character with Pour Monsieur, smelling effortlessly grown-up, discreet and rather conservative. The funniest comment I’ve seen online is that it ‘makes you smell ten years older. Richer, maybe; but older’, and I think that’s right, but now I’m older myself it’s nice to at least smell rich.

For a men’s perfume it has rather more floral ingredients than one might expect, including lily of the valley, jasmine and carnation, but they’re so subtly blended together that you’d never know. The flowers give it a little sweetness, but that’s balanced by the spicy, clove-scented edge of carnation. Equipage also contains a lot of orange, in the form of bergamot, squeezed from the peel of the Sicilian bergamot orange, Citrus bergamia, which is also used to flavour Earl Grey tea.

But that’s not all. This rich and complex fragrance also includes oakmoss (or a synthetic equivalent), which is actually a type of lichen that smells like a forest after rain; as it happens oakmoss also features in Pour Monsieur and Chanel No19. You might also be able to smell a touch of patchouli, that favourite 1970s fragrance, and perhaps a little Badedas-like pine – another forest touch.

There’s much, much more, which makes Equipage worth returning to again and again. It may not be the most avant-garde of fragrances, but if you want something reassuringly luxurious, it’s up there with the best.

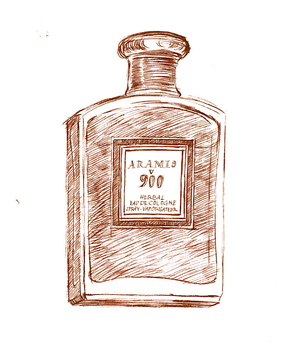

Aramis

Aramis 900

9 June, 2014

Aramis is one of those mid-market brands that seems to have been around for ever, and for that reason it’s often overlooked or, worse, looked down upon. Which is, I think, a shame, because there are some classic men’s perfumes in the range.

The all-men’s brand was launched in 1964 by Estée Lauder and her husband Joseph, with the eponymous Aramis (which I’ve reviewed here) as the first fragrance in the range. Though I’d always assumed the brand and the perfume were named after the character in The Three Musketeers, legend has it that it actually commemorates an obscure town in Armenia, which these days is transliterated as Yeremes. It sounds like a leg-pull, but then we’re also told that the Lauders were working with an Armenian designer at the time by the name of Arame Yeranyan, so you never know; I’ll let you know if I can get a definitive answer out of somebody.

Whatever the truth of the matter (and the perfume industry’s relationship with historical fact can sometimes be rather shaky), Aramis was a big success, and in 1973 it begat Aramis 900. Like the original Aramis it was created by Bernard Chant, a brilliant French perfumer who loved spicy, leathery fragrances, and it’s very much along those lines.

In fact, as it’s often been pointed out, if Aramis 900 hadn’t been marketed for men, it would have worked just as well as a woman’s scent – a good example of the obvious but too rarely grasped fact that in itself perfume has no gender. Just smell Clinique’s classic woman’s perfume, Aromatics Elixir, and you’ll see what I mean: it was also created by Bernard Chant and to many people smells identical to Aramis 900.

Aramis 900 is a deep, spicy, complicated scent, which makes most contemporary offerings smell weedy and washed-out by comparison. Today you’d only expect to find a men’s fragrance smelling this rich and complex in an expensive ‘exclusive’ range like Tom Ford or Armani Privée, but when it was launched it was aimed squarely at the middle market: these were not expensive perfumes.

Like the majority of other men’s perfumes, Aramis 900 includes lemon and bergamot, but among its more persistent and powerful ingredients are carnation, orris (iris) root, geranium, oakmoss, patchouli and vetiver, as well as rosewood oil, the natural form of which comes from an increasingly threatened rainforest tree, Dalbergia nigra.

Unlike most modern men’s perfumes, though, Aramis 900 has a predominantly floral scent, which to me smells like a mix of clove-scented carnation and old-fashioned rose. Though floral fragrances were popular with Victorian men, in 20th-century western culture they came to be thought of as ‘girly’, though for no particularly logical reason as far as I can see.

Luckily that didn’t stop perfumers from using floral ingredients in men’s perfumes, but in the case of Aramis 900 those flowery scents are brilliantly disguised by all sorts of other things, including a faintly ‘dirty’ smell that adds an oddly sexy extra to the mix. The forest-floor oakmoss and vetiver also stop it smelling sweet, while the carnation (despite being a flower) gives it the same kind of peppery spiciness that you can smell in Chanel’s Egoïste.

The amazing thing, to me, is that perfumes like Aramis 900 have been so cheap for so long, but in 2009 it seems to have dawned on Estée Lauder Inc what they had on their hands, and six perfumes in the Aramis range – including Aramis 900 – were relaunched and repackaged in matching bottles. Now priced at a less mass-market £60 and titled a ‘Gentleman’s Collection’, presumably the hope is that men who liked one fragrance might go on to collect the rest. Given the quality of most men’s fragrances today I’d say that wouldn’t be a bad idea.

Christian Dior

Eau Sauvage

3 March, 2014

How did I get this far without reviewing Eau Sauvage? And now that I’ve finally got round to reviewing it, how am I going to do justice to such an iconic perfume? OK, I’ve covered Eau Sauvage Extrême, but that’s a dreary spin-off and bears little relation to the glorious real thing. So, deep breath now, and here we go.

How did I get this far without reviewing Eau Sauvage? And now that I’ve finally got round to reviewing it, how am I going to do justice to such an iconic perfume? OK, I’ve covered Eau Sauvage Extrême, but that’s a dreary spin-off and bears little relation to the glorious real thing. So, deep breath now, and here we go.

Created by the legendary perfumer Edmond Roudnitska, Eau Sauvage was launched in 1966, and it’s deservedly regarded as one of the greatest men’s perfumes of all. Roudnitska’s took the idea of a classic men’s cologne, packing it full of fresh, zingy, clean-smelling bergamot-orange oil from southern Italy, but then he did a brilliant thing, by blending it with an equally strong dose of a recently patented chemical called Hedione.

Hedione smells of jasmine – as well it might, since it was discovered by chemists during the process of deconstructing the molecular bits and bobs that, collectively, create natural jasmine’s heady, narcotic scent. Hedione’s real name is methyl dihydrojasmonate, and it was first isolated in 1958 by Dr Edouard Demole, who worked for the giant Swiss perfume company Firmenich.

Methyl dihydrojasmonate has a light jasmine smell but also something citrusy about it, giving Edmond Roudnitska a jigsaw piece that fitted into both the bergamot orange of a man’s cologne, and also had something – but crucially not too much – of natural jasmine’s sumptuous, powerfully floral scent, which most men would have considered far too feminine to wear.

To this Roudnitska added lavender – another floral scent, though this time one whose herby, faintly sweaty character had made it a long-standing male favourite – as well as a range of other, less pronounced ingredients including oakmoss (originally extracted from a lichen that smells of forests after rain) and patchouli, which in small amounts, I’m guessing, enhances the dandified character of Eau Sauvage without pushing it over into full-on let-it-all-hang-out hippiness.

A great perfume is one thing, and an all-too-rare thing at that, but it’s rarer still for a brilliant perfume to be supported by great marketing and presented in a great bottle. And here Eau Sauvage struck lucky again. Christian Dior died in 1957 of a heart attack, but under Yves Saint Laurent and then Marc Bohan, the company commissioned a series of sexy, tongue-in-cheek yet effortlessly elegant posters from René Gruau, arguably the greatest fashion illustrator of the 20th century. They certainly added to Eau Sauvage’s masculine appeal.

Few of us think a great deal about the bottles that contain the perfume we use, though they do have their collectors (most of whom, oddly, seem to have lost interest in the perfumes they contain). But some bottles repay a second glance, and Eau Sauvage is one of them. It was designed by Pierre Camin, who worked for Baccarat and created many of the bottles for the perfumer François Coty, and its chic silver cap, embossed with a pattern of tiny overlapping scales like a freshly-caught mackerel, is said to have been inspired by the silver thimble that Christian Dior always had to hand. The diagonally ridged sides of the bottle itself, meanwhile, are supposed to resemble the regular pleats of a Dior dress, though that seems a bit of a stretch to me.

I could go on, but in the unlikely event that you’ve never smelled Eau Sauvage, or think of it as a tired old dinosaur, I’d rather you headed out and tried it for yourself. Just be careful, though, as Dior have experimented with different versions over the years, and what’s now called Eau Sauvage Extrême (which you’d think would just be a stronger version, as indeed it used to be) is now a completely different fragrance, pleasant enough in a dull way but far less exciting than the original.

My last words, though, go to Edmond Roudnitska, not only because he was a perfumer of genius, but also because he also had something so important to say about marketing that it should be tattooed on the forehead of every perfume-company PR.

‘The choice of a perfume,’ he said, ‘can only rest on the competence acquired by education of olfactive taste, by intelligent curiosity and by a desire to understand the WHY and the HOW of perfume. Instead, the public [is] given inexactitudes and banalities. The proper role of publicity is to assist in the formation of connoisseurs, who are the only worthwhile propagandists for perfume, and it is up to the perfumers to enlighten, orient and direct the publicity agents.’

Here’s to the day his dream comes true.